Somewhere in the Middle

Introduction

In my conversations, there was a recurring theme: labor productivity. The general sentiment was that the average Indonesia worker was unproductive and that this was a result of culture. But is this is actually true? If so, why?

Working Population

Perhaps the most well-known fact about Indonesia is that it has a huge working population. In 2021, the country had over 134 million in the workforce. To put that into an ASEAN context, that’s ~2.4x the size of Vietnam, ~3.0x the size of the Philippines, ~3.3x the size of Thailand, and ~7.9x the size of Malaysia.

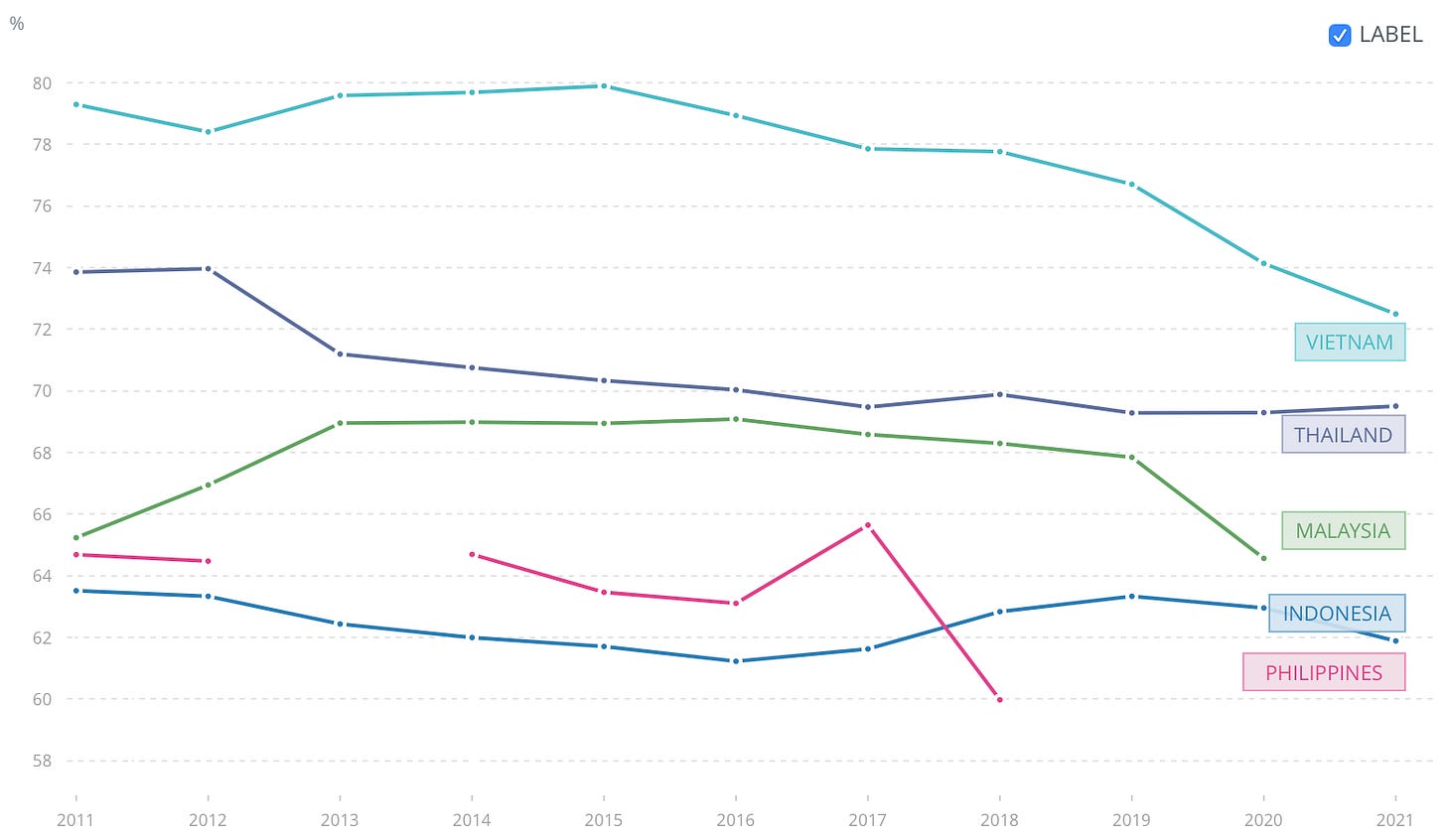

Despite Indonesia’s large working population, its workers are less educated next to ASEAN counterparts. Leaving aside the Philippines which did not have apples to apples data available for 2021, Indonesia falls in last place behind the economic powerhouses of the region.

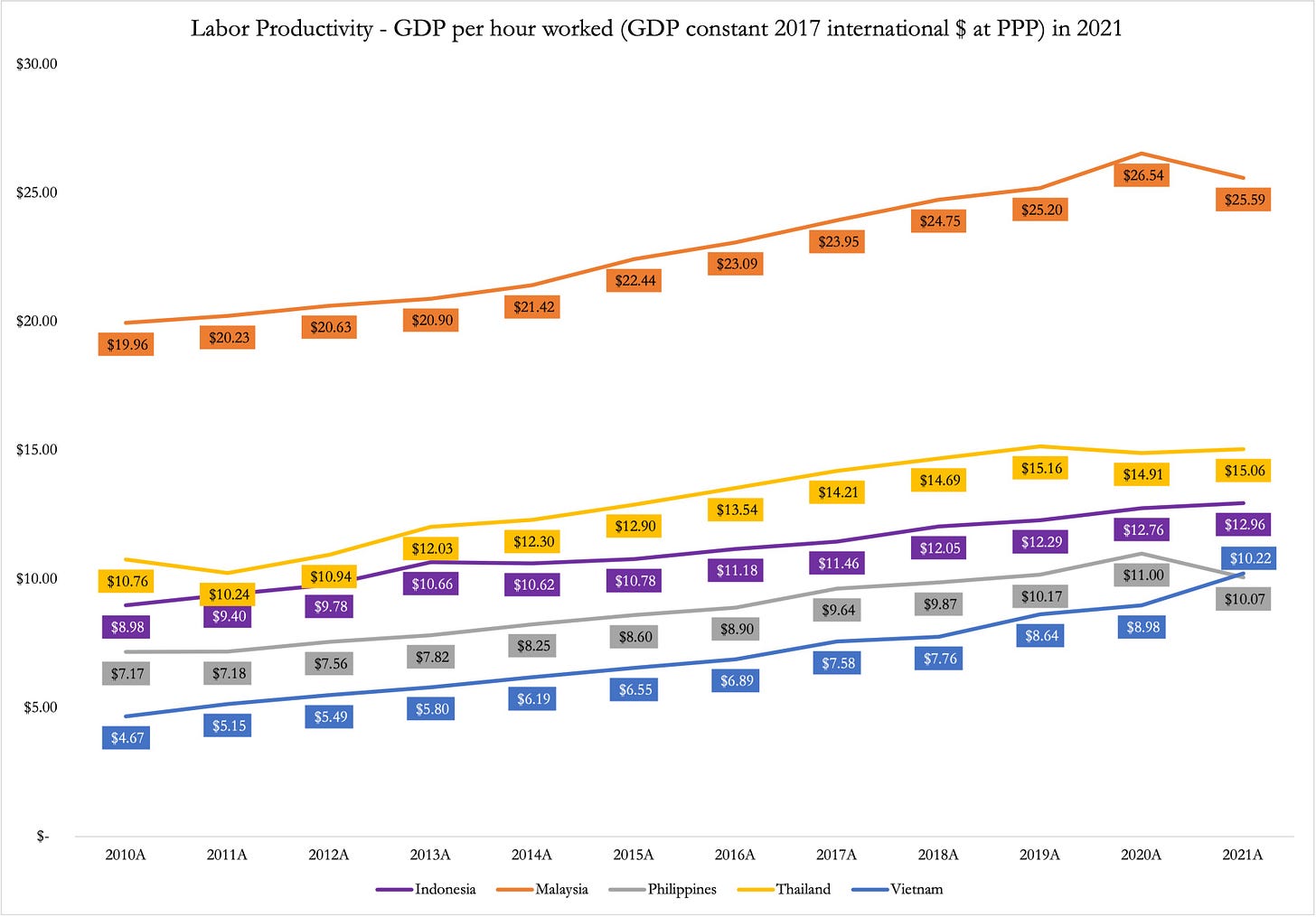

Labor Productivity

So… if Indonesia has a large workforce and a low level of educational attainment, its workers should not be that productive. However, Indonesia is in the middle of the pack.

Why the stereotype?

Unemployment Data

For one, Indonesia’s unemployment rate has been going down significantly. From its peak in 2007 at 8.1%, Indonesia has more than halved this in the last 14 years to 3.8%. This achievement stands out starkly compared to peers with the exception of the Philippines whose labor rebound from the Asian Financial Crisis is nothing short of impressive.

However, a larger base in the form of great employment numbers isn’t quite enough to demonstrate low productivity on the job. A more compelling reason is Indonesian policy.

Separation Payments

Indonesia has fairly unique labor laws with a strong leaning towards workers. Setting aside considerations of how beneficial this may be for labor, let’s consider how this might impact companies (employers) and economic activity more broadly.

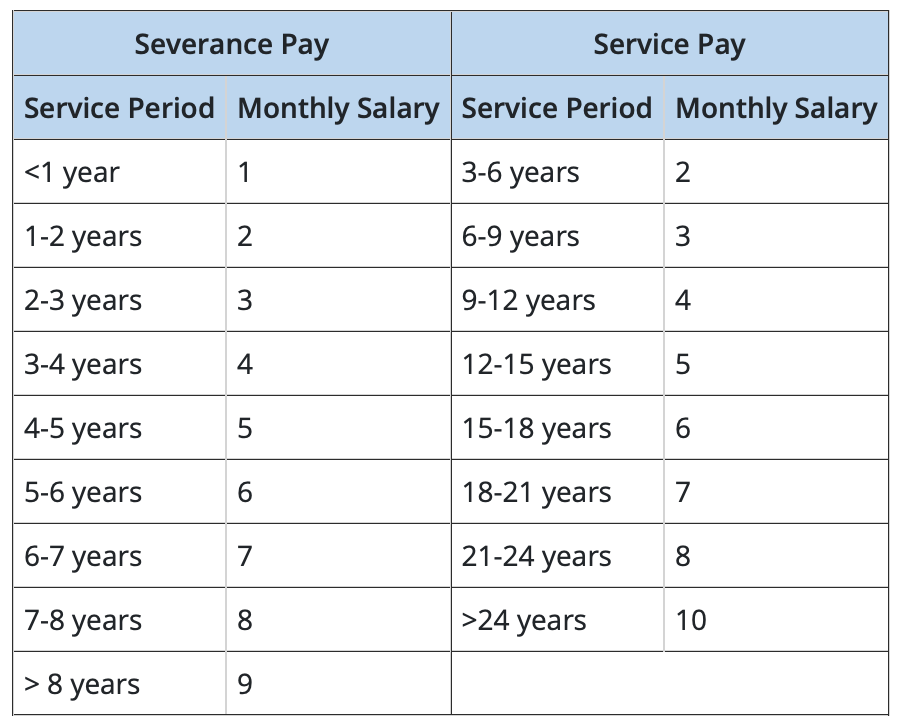

Separation payments can broadly be split into three categories: severance, service, and other.

Severance: All permanent employees are entitled to receive severance which is calculated as a predefined number of months * monthly salary.

Service: All permanent employees (that have worked at an employer for over three years) are entitled to receive service which is calculated as a predefined number of months * monthly salary.

Other: This includes remaining annual leave, repatriation expenses, other defined in employment agreements as well as applicable laws.

The chart below demonstrates what the predefined number of months are:

Based on the above, firing an employee of 6 years would be the same as paying that employee for 9 months (7 months of severance + 3 months of service) excluding other additional expenses. Once an employee hits 8 years, an employer would be paying at least 1 year’s worth of salary (9 months of severance and 3 years of service) as a separation expense.

Despite already leaning heavily towards workers, these separation laws are actually lenient to business owners in comparison to pre-Omnibus Law (formally passed in 2023). The chart below shows a couple of varying scenarios pre- and post- Omnibus Law.

What sticks out is the earnest reduction of merger/consolidation expenses —opening up opportunities for “accretive” transaction synergies. In the former regime, firing an employee of 8+ years due to M&A could equate to paying them 21+ months of salary — encouraging companies to keep both sets of employees in many cases. As a result, businesses were less incentivized to go through the painful yet necessary disruption of consolidation to boost margins and efficiency.

Now, let’s consider the supply side (labor) in the former regime.

If one could sustainably accrue downside protection at a rate of 1.33 months of salary per year, would that individual really want to go on the open job market? Further still, businesses were increasingly encouraged to keep workers — meaning that, workers could be nearly guaranteed lifetime employment or up to 32 months of separation payments if the business failed to keep them.

While I cannot speak for any given individual (and I haven’t worked in Indonesia), structurally it seems the prior labor regime actually rewarded middle performers. As a matter of course, most firms do not provide equity/options for non-white collar work. In addition, bonuses are generally one’s Tunjangan Hari Raya (“THR”) or ~ 1 month of salary.

Why outperform when you have downside protection and no upside participation?

Omnibus Law

Although this article focuses on separation payments, the Omnibus Law covers many topics outside of scope: such as the creation of a sovereign wealth fund, altering the minimum wage calculation (from sector minimums to geographic minimums), reducing mandatory paid leave, increasing the work week, lowering corporate taxation, easing firing regulation, encouraging foreign labor, reducing investment limitations, and reducing environmental limitations.

This article aims to only address separation payments as there have been plenty of articles academic, journalistic, political and otherwise exploring the other catalysts and their potential impacts.

From a theoretical standpoint, the easing of separation payments spurs productivity. However, it’s important to recognize the painful short-term consequences. Indonesia is a lower-middle income country and changes to labor laws impact those most vulnerable. It is no surprise, then, that the Omnibus Law has been divisive across Indonesia with protests occurring nationwide.

Beyond this, there are clearly some problematic aspects about the Omnibus Law namely, the anecdotal cyber troops, violent crackdown of protests, the means of passing the law which was ruled as “conditionally unconstitutional”, and then the subsequent work-around. Additionally, considerations such as corruption, oligarchy/rent-seeking, and religion in politics (to name a few) complicate the picture — meaning that even if the Omnibus Law is theoretically the right policy, effective implementation may not happen.

Happiness & Economic Prosperity

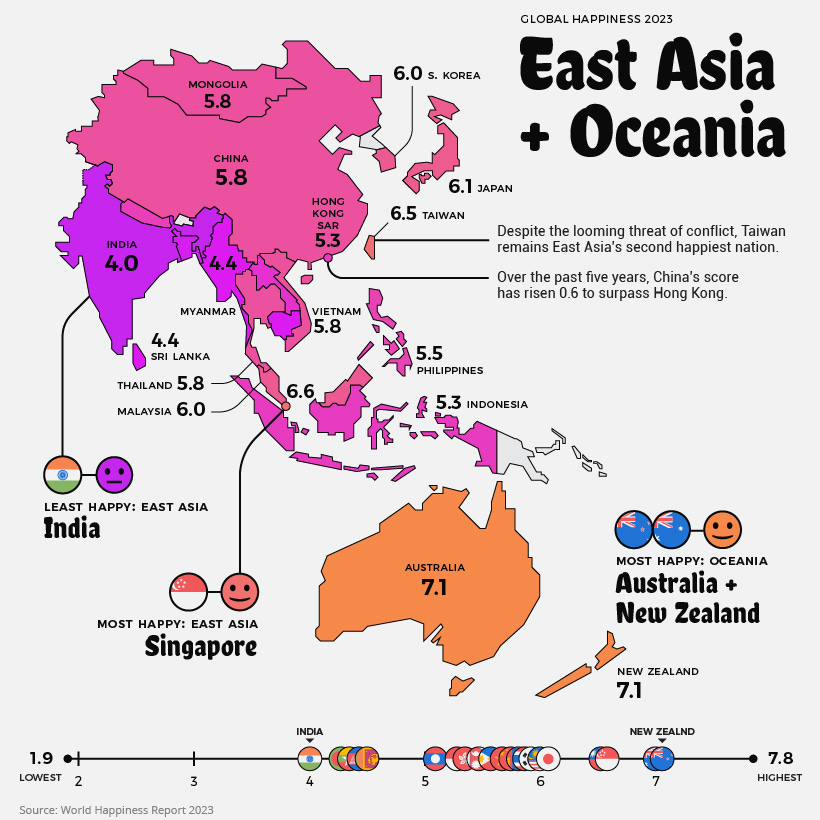

While I'm not suggesting that Indonesia become completely “pro-business” vis-à-vis labor laws, I do think it’s worth considering whether people are happy — especially if low labor productivity impacts the sustainability of long-term economic growth.

While Indonesia is happier than South Asia, it lags behind many of its ASEAN peers. Placed in a global context, Indonesia falls into the bottom half of the world vis-à-vis happiness at 86th place. Although I haven’t ran a regression, from a quick glance happiness in a global context is correlated with economic prosperity.

Perhaps it’s better for Indonesia to ease labor laws to encourage more risk-taking on the labor side while incentivizing consolidation. From an ideological level, labor might then allocate their time appropriately to careers that bring them happiness while driving up productivity and economic prosperity.

Closing Thoughts

Although Indonesian labor is not unproductive per se, it certainly isn’t where it could be. Consequently, the international stereotype that Indonesian workers are not efficient may hold weight. However, a quick analysis demonstrates that this is a result of policy and not “culture” (which has rather racist connotations).

I am interested to see how the next couple of years turn out post-Omnibus Law as industry has a bit more breathing room to consolidate and workers are less tied down to their existing roles by severance. Perhaps M&A while disruptive in the short-run will drive economic growth and, consequently, happiness. Imagine how many incremental tax dollars could be deployed into public goods if labor productivity were to skyrocket…

Found your distinction between culture and policy on perceived and actual labor productivity thought provoking. Good stuff!